What Works When Treating Acute

Malnutrition

| Global Health, Population, and Nutrition | |

A country faces a malnutrition crisis, such as famine. Organizations rush in, set up emergency services, and then dismantle the temporary operations. Historically, that’s been the approach to addressing acute malnutrition.

But when AED’s Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance II project, or FANTA-2, began working in Ghana, there was no crisis. Acute malnutrition was an ongoing life-threatening problem, affecting up to 8 percent of children under five years old.

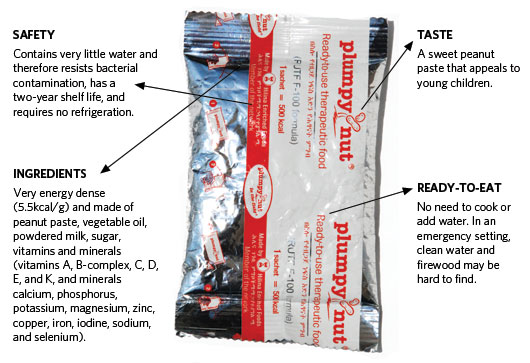

What’s a Plumpy’Nut? Plumpy’Nut is a ready-to-use therapeutic food. Nutriset, the manufacturer and a FANTA-2 partner, has established local production of Plumpy’Nut in a number of African countries. Along with other interventions, Plumpy’Nut is provided to severely malnourished babies who are over 6 months of age.

What’s a Plumpy’Nut? Plumpy’Nut is a ready-to-use therapeutic food. Nutriset, the manufacturer and a FANTA-2 partner, has established local production of Plumpy’Nut in a number of African countries. Along with other interventions, Plumpy’Nut is provided to severely malnourished babies who are over 6 months of age.

The problem required a comprehensive strategy, said Anne Swindale, director of FANTA-2. The project’s approach—called community-based management of acute malnutrition, or CMAM—includes volunteers who canvass their communities for malnourished children and refer them for additional care before their conditions worsen. Mothers bring children to nearby treatment sites where, in most cases, they receive ready-to-eat therapeutic food and information about malnutrition. FANTA-2, funded by USAID, provides training, guidance, and tools to help governments, health care providers, and communities integrate acute malnutrition management into their national health system.

“What strikes me the most is the gratitude we see from the health service providers,” Swindale said. “They didn’t have a way to help these kids before. But CMAM gives them something that works.”

For its efforts in CMAM and other areas, FANTA-2 draws on research about the most effective treatments and systems and translates that knowledge into training materials, strategies, and other tools governments and communities can use to address malnutrition themselves. Tim Quick of USAID’s Office of HIV/AIDS said FANTA-2 as a whole works because it helps governments structure an entire system for care.

“FANTA-2 doesn’t try to set up an office and muscle in,” he said. “It works with the whole of clinical services to make treatment more efficient.”

In 2008, at the request of the Ministry of Health and the Ghana Health Service, FANTA-2 established CMAM learning sites in three districts. More are being phased in as the government scales up in five of the country’s 10 regions.

This close partnership with the ministry is essential, Swindale said. “You have to be there, supporting the Ministry of Health,” she observed. “Their leadership is absolutely essential. FANTA-2’s activities really are led by the host country governments.”

A Sustainable Model

FANTA-2 supports Ghana’s expansion of CMAM by developing national guidelines for implementing it; training materials; data collection, monitoring and supervision tools; and methodologies to assess the program’s coverage. It also created a tool to help the government estimate the time, money, and other resources needed for expansion.

But the number one priority, said Alice Nkoroi, a FANTA-2 nutrition specialist based in Accra, Ghana, is building the skills of health care providers through training, mentoring, and coaching at all levels

Zambia

EARNEST MUYUNDA is the regional nutrition and HIV advisor for FANTA–2.

Most of our work here is about improving nutrition for people with HIV. More and more, we are seeing that good nutrition can help them respond to treatment better and resist other infections. It can improve their quality of life. But most HIV programs look at the clinical aspects and forget about nutrition. So we sit down with the government to think through what they need to make nutrition part of their HIV services: What strategies do they need? What kinds of programs? What’s the best way to train the health workers?

We have seen a lot of malnourished adults with HIV get a lot of information about treatment, but not enough about nutrition—studies show that many of them die within the first three months of treatment. But we are putting that missing piece in place. That’s really the motivation.

of the health system—national, regional, district, facility, and community. “When we’re working with partners, the main thing we have to do is give them skills to do their jobs more effectively,” she said.

Together with a government-funded coordinator, FANTA-2 instructs clinicians, nutritionists, and dietitians at the national level—who in turn teach trainers and service providers at the regional level—on how to deliver CMAM services.

“There’s continuous training” said Nkoroi. “With support from FANTA-2, the Ghana Health Service has formed a unit that coordinates and provides technical support at the national and regional levels. Our aim is to give people as much knowledge as possible and ensure that quality services are delivered to children with severe acute malnutrition.”

The train-the-trainer structure lets FANTA-2 create a country-specific, sustainable model to combat malnutrition. Of course, it takes time. Nkoroi said she has to be patient and move slowly to make sure people remain committed and the training sticks. But the investment pays off.

“Aid agencies leave in two or three years,” Nkoroi said. “We’re working with people who are there forever.”

‘Living Testimony’

Cynthia Obbu has seen FANTA-2’s impact firsthand. A district nutrition officer with the Ghana Health Service who was trained in CMAM by FANTA-2, Obbu taught volunteers how to identify children with acute malnutrition in their villages. Before FANTA-2 helped the Ghana Health Service introduce CMAM in her district, she said, clinics waited for patients to find them, but many parents didn’t know acute malnutrition could be diagnosed and treated.

Volunteers show pictures of malnutrition symptoms to parents, who then bring in the children who might need help. Using a special tape, a volunteer measures the circumference of a child’s upper arm to determine how malnourished the child is and whether to refer the child for treatment. In most cases, children go to a nearby outpatient site for examination, receive Plumpy’Nut—a nutrient-dense peanut paste in a ready-to-eat package, which parents can take home—and return for regular monitoring. Malnourished children who are sick and infants under six months old receive inpatient care.

“Many people see their kids changing overnight,” said Obbu, noting that some “marveled” at the improvement.

Obbu has seen children walk when they had never before taken a step. Mothers have more hope that they can help their children, she said. “They’re a living testimony. The cases we’re treating, the situations we’re managing—it’s wonderful. I feel confident—more than confident—that as long as we have supplies like ready-to-use food, and provided we do our work, malnutrition care can be one of our routines.”

For more information, contact Anne Swindale.

FANTA-2 is a project in the AED Global Health, Population, and Nutrition Group, which focuses on strengthening individual, community, and institutional actions to ensure the health and well–being of vulnerable populations. Programs to improve food security and lower malnutrition rates; combat the spread of HIV/AIDs, malaria, and other infectious diseases; and promote healthy lifestyles are currently being implemented in 28 countries in Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East.